Swimming in the Ridiculous

Clowns, Fools, Trickster, Outcasts, Wit and Wordplay

full articleShadow Shapes

The clown, the fool, and the outcast weave in and out of our everyday world. Unruly characters, members of the comic genus, they fart in the middle of our most serious discourse, upset our apple carts and, making us laugh, worm their way into our hearts. Their presence offers us two invaluable gifts: an understanding of realities beyond common sense; and a tolerance of chance, catastrophe, and flux.

Trying to think in logical types and strict categories, we make ourselves prey for the imps of the indeterminate. Trying to escape ambivalence, Oedipus-like we run right into it. – Geoffrey Galt Harpham, On the Grotesque

Folly, nonsense, illogic, the grotesque, sin and evil: these are shadows cast by the great virtues of wisdom, sense, logic, beauty, and goodness. The shadow shapes bring to mind that catchall drawer that may be found in even the tidiest of households, the I-don’t-know-what-to-do-with-these-things drawer.

Scientists are coming to realize that the human brain is neurologically wired to make systems and patterns; we perceive and immediately try to organize what we perceive into categories. But life has a way of presenting us with experiences that we can’t fit into familiar categories! If the experience is benign, we laugh and say, that just doesn’t make any sense: it’s nonsense! The shadow category of nonsense, like the catchall drawer, provides us with a place to put things that confuse us. At the other extreme, an evil or grotesque experience defies our understanding. Thus we refer to people who kill their children as inhuman monsters: and it gives us some comfort to have a category in which to put them.

As Mary Douglas reminds us in Purity and Danger,

It is not always an unpleasant experience to confront ambiguity…. There is a whole gradient on which laughter, revulsion and shock belong at different points and intensities. The experience can be stimulating. The richness of poetry depends on the use of ambiguity…. Aesthetic pleasure arises from the perceiving of inarticulate forms.

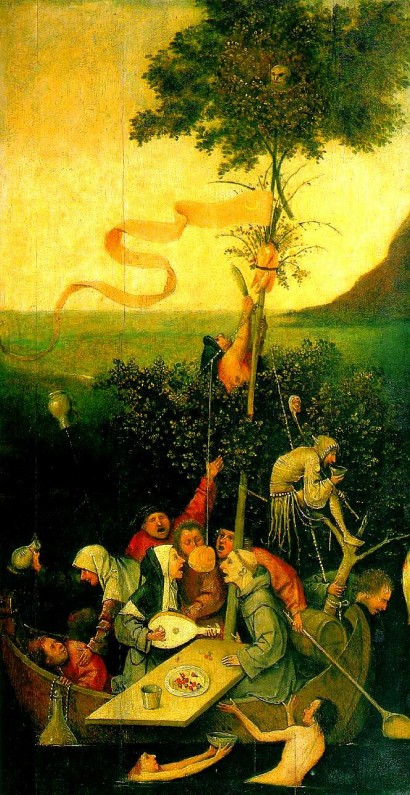

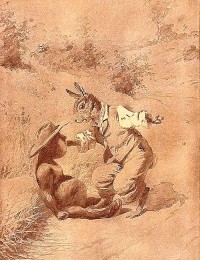

The spectrum from humor to disgust appears in comedy, parody, caricature, buffoons, the carnivalesque, and the grotesque. We take a certain pleasure in art that addresses unwieldy human experience, for it amuses, challenges, and educates us. Goya, Shakespeare’s fools and clowns, Brer Rabbit, Dada, the surrealists, Quasimodo, Bosch, Breughal the elder, Daumier, Hogarth, marginal doodles on Medieval manuscripts, Roadrunner and Bugs Bunny cartoons, gargoyles and sheela na gigs, the Marx Brothers, Don Quijote and Sancho Panza, Gulietta Masina in La Strada , Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Lenny Bruce, Lucille Ball, W.C. Fields, Monty Python, Gracie Allen, Woody Allen, Richard Pryor—they all belong, in Harpham’s term, to the “species of confusion.” Each embodies a lack of uprightness, an impurity, an abnormality. We begin to understand formlessness when we apply a bit of order to it. Then we find in-versions, sub-versions and ob-versions: high becomes low, back becomes front. Our actions, intentions, bodies, clothes, and words are turned inside out. And so we are shown an expanded understanding of ourselves.

Clown

How can one better magnify the Almighty than by sniggering with him at his little jokes, particularly the poorer ones? –Samuel Beckett, Happy Days

The clown inhabits folly in a charming way, giving us a chance to delight in non-heroic moments: the lack of order in body and mind; a deficit of influence in the world; and the want of beauty. The Clown is disproportionate in shape and manner, but tumbles through life with a certain openness and even grace, inspiring us to relinquish some of our own death grip on control.

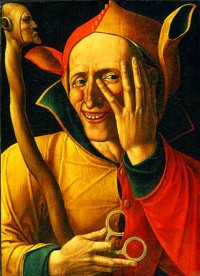

Fool

I wear not motley in my brain! – Feste (The Fool) Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

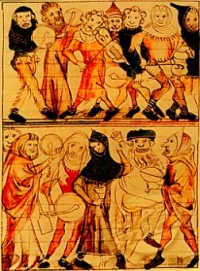

The Fool lays bare the folly of the world,often challenging those in power. His status as a non-entity (he’s only afool!) serves as both protection and provocation. The pied or motley costume in the European tradition reflects the patchwork of skills the professional Fool uses to reveal a sometimes-bitter truth. With a little ditty to wrap it in nonsense, some juggling to keep multiple ideas in the air, and a sharp mind to turn words inside out, the Fool must be ready to make a quick exit if the barbs get too sharp!

The Fool lays bare the folly of the world,often challenging those in power. His status as a non-entity (he’s only afool!) serves as both protection and provocation. The pied or motley costume in the European tradition reflects the patchwork of skills the professional Fool uses to reveal a sometimes-bitter truth. With a little ditty to wrap it in nonsense, some juggling to keep multiple ideas in the air, and a sharp mind to turn words inside out, the Fool must be ready to make a quick exit if the barbs get too sharp!

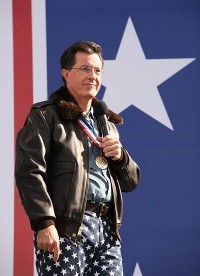

There are vibrant fools working right now: Stephen Colbert, for instance, uncovers the absurd with his pundit persona on The Colbert Report, his mock news program. Colbert regularly plays with language; several of his neologisms, such as truthiness, have passed into our language.

Now I’m sure some of the “word police,” the “wordinistas” over at Webster’s are gonna say, “Hey, that’s not a word!” Well, anybody who knows me knows I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist, constantly telling us what is or isn’t true, or what did or didn’t happen. (“The Colbert Report,” 10/17/05 )

The word quickly caught the public’s imagination and truthiness was named 2006 Word of the Year by dictionary publisher Merriam-Webster. Speaking truth to power as edgily as the ancient fools addressed the kings, Colbert’s audacious performance at the 2006 Press Association Dinner, in front of President and Mrs. Bush, was a tour de force!

Trickster

Coyote is excrement-corpse-fool-gambler-imitator-witch-hero-savior-god. – Karl Luckert, Navaho Coyote Tales

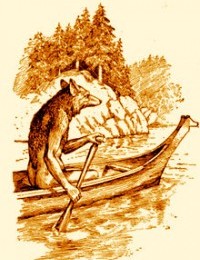

Behind the curtains and through the forests lopes the Trickster, a shadow figure of the gods. Found in cultures around the world, Tricksters embody wiliness and ambiguity. Often they address our appetites for food and sex. Sometimes they trip over their great sexual prowess, or do some gender shifting. Prometheus is a trickster; he tries to deceive Zeus and fails, then steals fire and gives it to humans. Tricksters sometimes assume animal and hybrid forms. Animal trickster figures include Coyote, Hare, and Raven in American Indian cultures; Fox in European folklore; Rabbit in African-American tales; and Tortoise, Spider, and Frog in African folklore. These characters violate customs and taboos, tromping over established ways. Tricksters seem less clever than animals with defined instincts; they make obvious mistakes; but they also are inventive, resilient, and adaptive, imitating habits of others to get out of big scrapes. “These myths suggest that blending natural history and mental phenomena is not an unthinking conflation,” suggests Lewis Hyde. “To learn about intelligence from the meat-thief Coyote is to know that we are embodied thinkers.”

Outcast

You are one of us! – The Freaks, addressing the Trapeze Artist, in Tod Browning, The Freaks

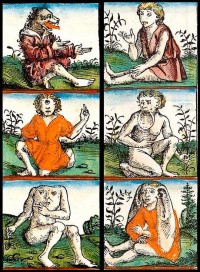

“The Outsider is [someone] who has awakened to chaos,” Colin Wilson writes. Whether by withdrawing voluntarily, or being exiled from society, the Outcast has a perspective on human behavior and customs that those on the inside do not have. When King Lear is cast out from civilization and wanders into the wilderness, his Fool can no longer help or comfort him. Instead it is the madman, Poor Tom, who illuminates Lear’s understanding. “Is man no more than this?” asks Lear. “Thou art the thing itself; unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art.”

The figures who embody the outcast perspective—the mad, the grotesque, the humpback and otherly misshapen, ascetics sitting on mountaintops, pariahs, malcontents, wanderers, dispossessed, bag people—hold up a mirror and reflect back to us our twisted, stunted, and deformed selves. These characters offer a harrowing view of life on the margin: Shakespeare’s Timon, the paintings of Goya and Bacon, the writings of Artaud, Dostoevsky, Kafka, and the inspired rants of the schizophrenic, homeless man on my street. “When we call a person ‘mad,’” Peter J. Wilson admits, “we acknowledge that by the evidence of his behavior he has reached a point at which he is beyond our power to control.” As cut off as the Outcast is from the benefits of companionship, her unsocial behavior and unmitigated expression of freedom can humble us.

Carnival

Mardi Gras is a controlled riot. People just go totally berserk, lose all their inhibitions. They forget everything they’ve ever been taught in their life. – Sgt. Billy Roth, New Orleans Police Department, Cops

The collective embodiment of the ridiculous appears throughout history and across cultures in folk celebrations, the chaos of Charivari, and carnivals of all kinds. During these events, individuals are permitted to let go of their inhibitions. Social inequities are challenged through parody and satire. In a powerful upending of sacred hierarchy during Europe’s late medieval period, for example, the Feast of Fools annually appointed a Lord of Misrule, who came riding backwards into the church on a donkey, preceded by acolytes waving censors of burning donkey dung.

Every year in Basel, as part of a three-day Carnival, scores of lantern-like floats, decorated with pictures lampooning local and international issues, parade into a main square. Local groups spend months preparing these elaborate floats, and pen caustic poems to send their points home. Bands of drums and fifes, in coordinated costumes and masks, accompany them. Music and rhythm are the driving forces for a shuddering undulation of sensuality and cross-dressing each year in Brazil. Even Halloween in the U.S., though now grossly commodified, offers young and old people the possibilities of disguise, pranks, satire, and social commentary: Trick or treat!

Lotschental is a small village in Switzerland where each winter the power of the vast mountains takes shape in the visitation of the Tschaggata. These crudely masked figures are animated mostly by local boys, disguised to be unrecognizable. In addition to large, crude, grotesque wooden masks, they wear fur skins and belts with huge cowbells phallic and deafening. The Tschaggata are funny and also scary; they exude an exciting and almost dangerous sexual energy. They harass and chase you. They throw snow at you, pull you down, rub snow in your face: the rule is, anything short of drawing blood. If you’re in a café and they come in with a deafening noise and sit down next to you, they may take your food, hug you – and you have to put up with it, even enjoy it! All over the Alps, people have created shapes to articulate the dark chaotic side of life, in balance with the orderliness and self-control for which the region is also known.

Lotschental is a small village in Switzerland where each winter the power of the vast mountains takes shape in the visitation of the Tschaggata. These crudely masked figures are animated mostly by local boys, disguised to be unrecognizable. In addition to large, crude, grotesque wooden masks, they wear fur skins and belts with huge cowbells phallic and deafening. The Tschaggata are funny and also scary; they exude an exciting and almost dangerous sexual energy. They harass and chase you. They throw snow at you, pull you down, rub snow in your face: the rule is, anything short of drawing blood. If you’re in a café and they come in with a deafening noise and sit down next to you, they may take your food, hug you – and you have to put up with it, even enjoy it! All over the Alps, people have created shapes to articulate the dark chaotic side of life, in balance with the orderliness and self-control for which the region is also known.

The Usefulness of Absurdity

HAMM: We’re not beginning to…to…mean something? CLOV: Mean something! You and I, mean something! (Brief laugh.) Ah that’s a good one! – Samuel Beckett, Endgame

According to recent studies in neurology, when people are put in situations in which they can’t discern an order, the brain releases neurotransmitters that excite the brain to go further, to figure something out. According to Mary Douglas, “there are several ways of treating anomalies” in our experience. We can ignore or condemn them, or “we can deliberately confront the anomaly and…create a new pattern of reality in which it has a place.”

As we move closer to all the shadow shapes I have been discussing, we laugh with nervousness or amusement or even horror. From the muffled titter to uncontrolled hooting over an open grave, we loosen the hold that rational constraints have on us and we open out into a wider flow of liberating chaos. We experience a positive boost from laughter, which releases toxins and results in an unusual joining of right and left-brain over the bridge of the corpus callosum, stimulating our parasympathetic nervous system, which governs recuperation. Now we have modern science to support what we have known for ages: by exploring this terrain of folly – and practicing belly laughs – we begin to heal!

Wit & Wordplay

- The pun is the verbal equivalent of the animal hybrid, the unlikely combination of two thoughts. It is thereby kin to the grotesque of the monstrous races.

One morning I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got into my pajamas I’ll never know. – Groucho Marx, Adventure in Africa

Curiouser and curiouser. – Alice, Alice in Wonderland

The shadow shapes contribute to our understanding of the uncontrollable, the chaotic, and the crooked. They do so by every means possible: exaggerated physicality, reordering of social habits, and of course, language.

As children learning to speak and communicate, we delight in language: the sensual pleasure of the infant blowing through her lips, rhythmic nursery rhymes, onomatopoeia, the joyful twists of meaning in riddles and knock-knock jokes. We revel in its power, its magic, its multi-dimensions. But as we grow older, we are encouraged to use a language that is more concrete, with particular, determined meanings; rhyme and metaphor are exiled to slim volumes of poetry.

Puns, rhymes, chop logic and higgledy-piggledy nonsense immediately draw attention to the gaps, shortcomings, and sacrifices we make in the course of creating our social selves — dutifully following agreed-upon rules to make communication efficient and meaningful. Wordplay removes any false security about univocal meaning. It also prevents us from assuming that language is natural and unconstructed. To play with language is to reclaim its mercurial nature, its movement, and to empower ourselves as humans.

© Merry Conway, 2011. All rights reserved